By BloggerKhan

Posted in General Business & Technology | Tags : anchor price, anchoring, Arbitrary Coherence, Dan Ariely, memory of old price, Predictably Irrational, relative price, scarcity, The fallacy of supply & demand

Here is another topic that I want to share with you from the book ‘Predictably Irrational‘ by Dan Ariely. Some of the examples are mine and the errors if any are all mine.

The fallacy of supply & demand:

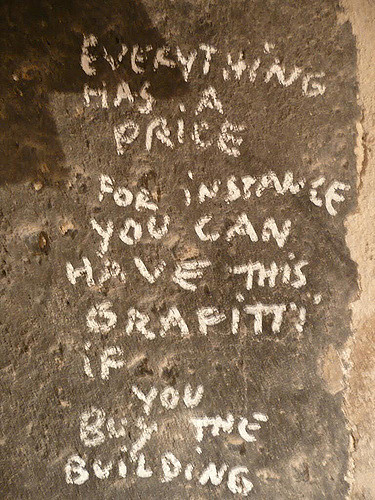

Conventional economics would like us to believe that human beings are rational and where supply and demand meet, the price is set. Reality is different.

Scarcity:

We covet what is scarce whether we truly understand it’s worth or not. That’s why Tahitian black pearls sell at a premium. That’s why the car salesman says “this is the last one on the lot with these features” and the realtor says “two other families are interested in this house, one is talking to his bank right now”.

Anchoring:

I am blending excerpts from the book Predictably Irrational with excerpts from Wikipedia and my own explanations to help make it clearer. For those of us in the marketing profession, it is important to understand anchoring. Don’t rush this topic, read it, re-read it and let it sink in.

Anchoring or focalism is a cognitive bias that describes the common human tendency to rely too heavily, or “anchor,” on one trait or piece of information when making decisions. (Wikipedia)

Anchoring and adjustment is a psychological heuristic that influences the way people intuitively assess probabilities. According to this heuristic, people start with an implicitly suggested reference point (the “anchor”) and make adjustments to it to reach their estimate. A person begins with a first approximation (anchor) and then makes incremental adjustments based on additional information. (Wikipedia)

The anchoring and adjustment heuristic was first theorized by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman. In one of their first studies, the two showed that when asked to guess the percentage of African nations which are members of the United Nations, people who were first asked “Was it more or less than 10%?” guessed lower values (25% on average) than those who had been asked if it was more or less than 65% (45% on average). The pattern has held in other experiments for a wide variety of different subjects of estimation. Others have suggested that anchoring and adjustment affects other kinds of estimates, like perceptions of fair prices and good deals. (Wikipedia)

Some experts say that these findings suggest that in a negotiation, participants should begin from extreme initial positions.

As a second example, an audience is first asked to write the last two digits of their social security number and consider whether they would pay this number of dollars for items whose value they did not know, such as wine, chocolate and computer equipment. They were then asked to bid for these items, with the result that the audience members with higher two-digit numbers would submit bids that were between 60 percent and 120 percent higher than those with the lower social security numbers, which had become their anchor.

Anchor price is not necessarily the sticker price of an item. Anchor price is a number that you make people consider. When people have thought about or considered or remembered a higher number, they tend to pay higher. Their mind has been primed for a higher number.

If you have a furniture showroom, display the expensive furniture in the front and the less expensive ones deeper in the store. Customers may not buy the more expensive furniture but they will end up paying more for the items they actually buy even though those items could have been bought for a little less at another “cheaper store”. You have created the suggested reference point (the “anchor”) at a higher price point with your expensive furniture at the entrance. Your internal decor better match the value you want to project in order to be consistent.

Arbitrary Coherence: Initial prices are largely arbitrary and can be influenced by responses to random questions but once prices are established in our minds, they shape not only what we are willing to pay for an item but also how much we are willing to pay for related products (this makes them coherent).

We don’t necessarily make rational decisions. We decide on gut feelings and what we desire and then try to rationalize. Our decisions are generally based on our perception of ourselves and our experiences.

Our first impression (in this case price) lasts a while and lingers over several subsequent decisions over a long time.

Memory about old price:

People who move from one state to another associate a similar price for their new home as they did in their older home state. So Californians end up overpaying when they move to Texas.

People react to a price change if they remember the old price. If not, remind them. For example; when we were selling refurbished laptops, we would make sure that we mention the original price, e.g., Refurbished IBM ThinkPad 770X $500, (original Retail Price $2500). The customer loved the fact that he saved $2000 over the original price even though we were selling the refurbished laptop pretty much at the same price as our competitors, in fact a little higher.

If an item is selling at $500 and you offer a 20% discount, that is a $100 saving. Advertize the price as $500 – $100 discount =$ 400. That will result in better sales than just changing the price to $400. The older price becomes the reference price. IBM regularly prices it’s new mainframes at a high price and those who absolutely have to have the most throughput and computing power buy at that premium price. Four to six months later, they discount the line and the rest of the corporate world rushes in. At the same time they announce a more premium model for their power hungry users. Apple did the same with it’s iPhones. Six months after introduction, it dropped the price by $200 and the masses flocked in. What a deal! This would not have been as effective if they had started off at a lower price.

Even in relationships, initially playing hard to get works. We covet what is scarce, what is hard to get, what is at a premium. It raises our perceived value of the desired item and when we finally get it, we are happier. Irrational? You bet.

No comments yet.